Researchers have discovered a sea of water trapped among the sediments and rocks of a lost volcanic plateau that now lies deep within the Earth’s crust. Water lies three miles below the ocean floor off the coast of New Zealand, where it may be dampening a powerful earthquake fault facing the country’s North Island, according to 3D seismic imagery.

The fault is known to cause slow earthquakes, called slow slip events. They can harmlessly release tectonic pressure accumulated over days and weeks. Scientists want to know why these failures occur more frequently in some faults than in others.

Most slow-slip earthquakes are believed to be associated with buried water. But until now there was no direct geological evidence that such a large water reservoir existed along this fault line in New Zealand.

“We can’t see deep enough yet to determine the exact impact on the fault, but we can see that the amount of water coming in here is actually much higher than normal,” said lead study author Andrew Gase, who led the study. University of Texas Institute of Geophysics (UTIG). The research was published in the journal Science Developments and based on seismic cruises and scientific ocean drilling conducted by UTIG researchers.

Gase, now a postdoctoral researcher at Western Washington University, is calling for deeper drilling to find where the water entered so that researchers can determine whether the water affected the pressure around the fault — important information that could lead to a better understanding of large earthquakes, he said.

The area where the researchers found the water is part of a massive volcanic field formed 125 million years ago when a lava cloud the size of the United States broke through the Earth’s surface in the Pacific Ocean. This event was one of the largest known volcanic eruptions on Earth, lasting several million years.

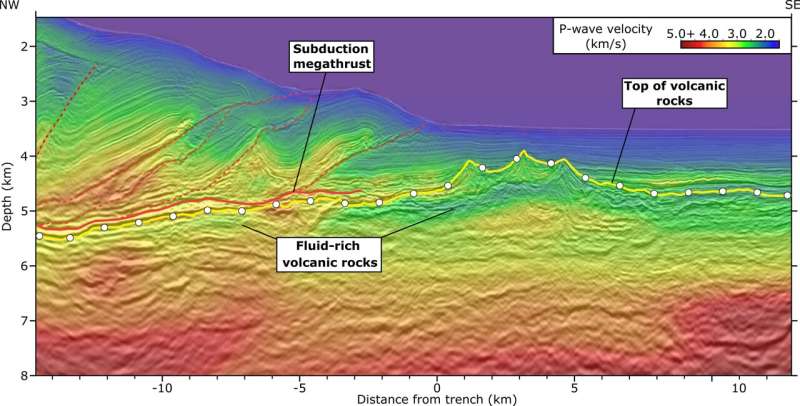

Gaz used seismic scans to create a 3D image of the ancient volcanic plateau; here he saw thick, layered sediments surrounding buried volcanoes. His collaborators at UTIG performed laboratory experiments on samples of volcanic rock cores and found that water makes up almost half of the volume.

“Normal ocean crust, when it is about 7 or 10 million years old, should contain much less water,” he said. In seismic scans, the ocean crust was ten times older but much wetter.

The gas suggests that shallow seas where eruptions occur erode some volcanoes into porous, fissured rocks, storing water as an aquifer when buried. Over time, stone and rock fragments turned into clay and held even more water.

The discovery is important because scientists believe groundwater pressure may be a key component in creating conditions that release tectonic stress through slow earthquakes. This usually occurs when water-rich sediments are buried by a fault, trapping water underground. However, the New Zealand fault contains little of this typical ocean sediment. Instead, researchers believe that ancient volcanoes and metamorphosed rocks (now clay) carried large amounts of water and absorbed it through faults.

UTIG director Damian Saffer, co-author of the study and co-leading scientist of the scientific drilling mission, said the results suggest that other earthquake faults around the world may be in similar situations.

“This is a really clear example of the correlation between fluids and the way tectonic faults move, including earthquake behavior,” he said. “This is what we assumed based on laboratory experiments and predicted from some computer simulations, but there are few open-field experiments to test this at the scale of plate tectonics.”

Source: Port Altele