The Tibetan Empire was the world’s highest empire at 4,000 meters above sea level and flourished from 618 to 877 AD. It is home to about 10 million people and spans an area of about 4.6 million km.2 It extends in eastern and central Asia, as far as northern India.

The development of the empire is incredible, given the unfavorable conditions for population growth, including hypoxia, where the oxygen concentration is 40% lower than sea level. However, its collapse in the 9th century has not been fully studied, and a new study has been published. Quaternary Science Reviews, It aims to explain the role climate may have played in the end of a great civilization.

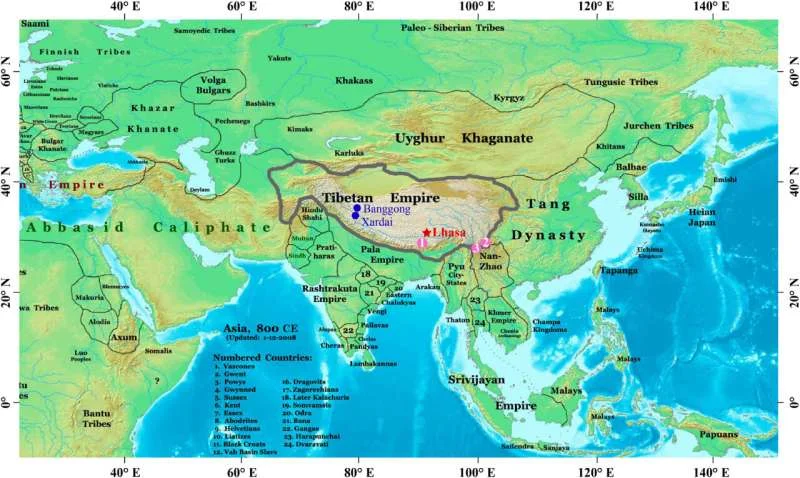

Zhitong Chen of the Tibetan Plateau Research Institute in China and his colleagues turned to the geological record (paleolimnology) of lake sediments to determine how the environment changed 12 centuries ago. Xardai Co’s freshwater lake sediments preserve remnants of microscopic single-celled algae known as diatoms; The research team notes that there is a significant transition from planktonic species (those that drift in a body of water, usually closer to the surface) to benthic forms. (live near the bottom of the lake). This is interpreted as a transition to drier conditions, causing lake levels to drop.

There is a clear pattern of high lake levels, indicating that warm and humid conditions prevailed during the rise and apex of the Tibetan Empire. AD 600-800 e., before conditions worsened until a severe drought that coincided with the collapse of the empire c. AD 800-877 Chen and his collaborators attribute the drought to the possibility of crop shortages; This leads to the collapse of empires, leading to social unrest among the population, as well as religious and political difficulties.

The Tibetan Plateau is extremely sensitive to climate change, with altitude, temperature, and precipitation fluctuations significantly different from Earth’s average values. Working lake Xardai Co is usually covered with ice from November to April, but with local temperature differences between -12.1 °C and 14.1 °C and annual precipitation of 71 mm. These factors have a significant impact on lake levels and therefore on the organisms living in the lake.

Previous approx. In 800 AD, diatom communities were dominated by two planktonic forms: Lindavia Radiosa and Lindavia ocellata, and to a lesser extent Amphora pediculus and Amphora inariensis. Here, the ratio of planktonic to benthic forms peaked in wet conditions, causing the lake level to rise.

However, the milestone in 800 AD is the rapid growth of the benthic diatoms Amphora pediculus and Amphora inariensis, while the aforementioned Lindavia radiosa and Lindavia ocellata decline in open waters. This diatom community existed until 1300 AD. For example, when the lake level started to rise again during the Little Ice Age.

The data were compared with other paleo-environmental indicators on the Tibetan Plateau, confirming that these climate changes were consistent across the region, not just in the study lake. These included precipitation records from Xardai Co, a second lake located 50 km north of Banggong Co, and temperature records from China.

Crop cultivation in the Yarlung Zangbo River Valley and cattle grazing in the Kantang Plateau, as well as agriculture and livestock were the dominant livelihoods when we relate climate change to the effects on the population of the period. During the expansion of the empire, warmth and rain facilitated the growing of crops and wild pastures for grazing animals, increasing the altitude at which they could be grown. Horses, goats, and yaks are grazing animals and were important to Tibet’s trading economy.

However, a relatively sudden decrease in climate for about 60-70 years will inhibit plant growth and lead to reduced grazing in agriculture and livestock. This would have a critical impact on the survival of the population due to food shortages and the economic well-being of a trade-dependent empire. Social unrest likely followed the disintegration of various political agendas and eventually led to the end of the Tibetan Empire.

Today, agriculture and livestock provide more than half of Tibet’s annual income; therefore, understanding the impact of climate on communities living in harsh environments is crucial to ensuring that they not only survive but thrive. Source

Source: Port Altele