A team of astrophysicists led by scientists from the Institute for Advanced Study has developed an innovative technique to search for the light echo of a black hole. Their new method, which will make it easier to measure the mass and spin of black holes, is a major step forward because it works independently of many other methods by which scientists have studied these parameters in the past.

Research, It was published inside Astrophysics Journal Lettersoffers a method that could provide direct evidence of orbiting photons black holes Due to an effect known as “gravitational lensing”.

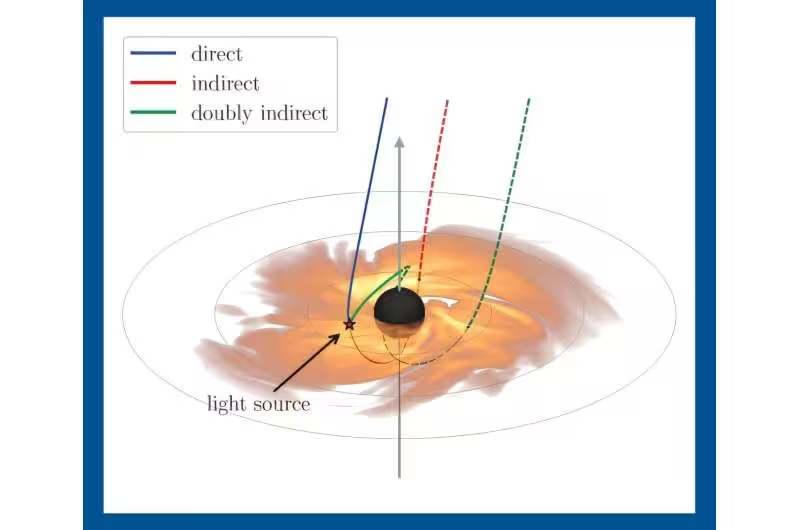

Gravitational lensing occurs when light passes near a black hole and its path is bent by the black hole’s strong gravitational field. This effect allows light to take multiple paths from its source to an observer on Earth: Some light rays may follow a straight path, while others may circle the black hole one or more times before reaching us. This means that light from the same source may arrive at different times, resulting in an “echo”.

“It has been theorized for years that light orbits black holes causing echoes, but such echoes have not yet been measured,” says study lead author George N. Wong, a Frank and Peggy Teplin Scholar in the institute’s School of Life Sciences. and Associate Scientist at the Princeton Gravity Initiative at Princeton University. “Our method provides a blueprint for making these measurements that could potentially revolutionize our understanding of black hole physics.”

This technique makes it possible to separate weak echo signatures from stronger direct light collected by well-known interferometric telescopes such as the Event Horizon Telescope. Both Wong and one of his co-authors, Leah Medeiros, a visiting researcher in the Institute’s School of Natural Sciences and a NASA Einstein Fellow at Princeton University, have worked extensively with the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration.

To test their technique, Wong and Medeiros worked with James Stone, a professor in the School of Life Sciences, and Alejandro Cárdenas-Avendaño, a research scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory and a former research assistant at Princeton University, to demonstrate high performance. Resolution simulations that create tens of thousands of “snapshots” of light orbiting a supermassive black hole, similar to the black hole at the center of the M87 (M87*) galaxy, located about 55 million light-years from Earth.

Using these simulations, the team showed that their method could directly determine the echo delay time in simulated data. They believe their technique can be applied to other black holes other than M87*.

“This method will not only verify when light is measured in the black hole’s orbit, but will also provide a new tool for measuring fundamental properties of the black hole,” explains Medeiros.

It is important to understand these features. “Black holes play an important role in shaping the evolution of the universe,” says Wong. “While we often focus on how black holes attract objects, they also emit large amounts of energy into their surroundings.

“They play an important role in the development of galaxies; they influence how, when and where stars form, and they help determine how the structure of the galaxy evolves. Knowing the distribution of black hole masses and spins, and how this distribution changes over time, will greatly improve our understanding of the universe.”

It is difficult to measure the mass or spin of a black hole. Wong notes that the nature of the accretion disk, that is, the rotating nature of hot gas and other material spinning inward towards the black hole, could “confuse” the measurements. But light echoes provide independent measurements of mass and spin, and having multiple measurements allows us to make an estimate of the parameters “that we can actually believe in,” says Medeiros.

Detecting light echoes could also allow scientists to better test Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity. “We use this technique to tell us, ‘Hey, this is weird!’ “Analysis of such data could help us test whether black holes really fit into general relativity,” adds Medeiros.

The team’s results show that it is possible to detect echoes with a pair of telescopes (one on Earth, the other in space) working together to perform what can be described as “very long baseline interferometry.” Such an interferometric mission would only need to be “modest,” Wong says. The technique they used provides a useful and practical method for collecting important and reliable information about black holes.

Source: Port Altele