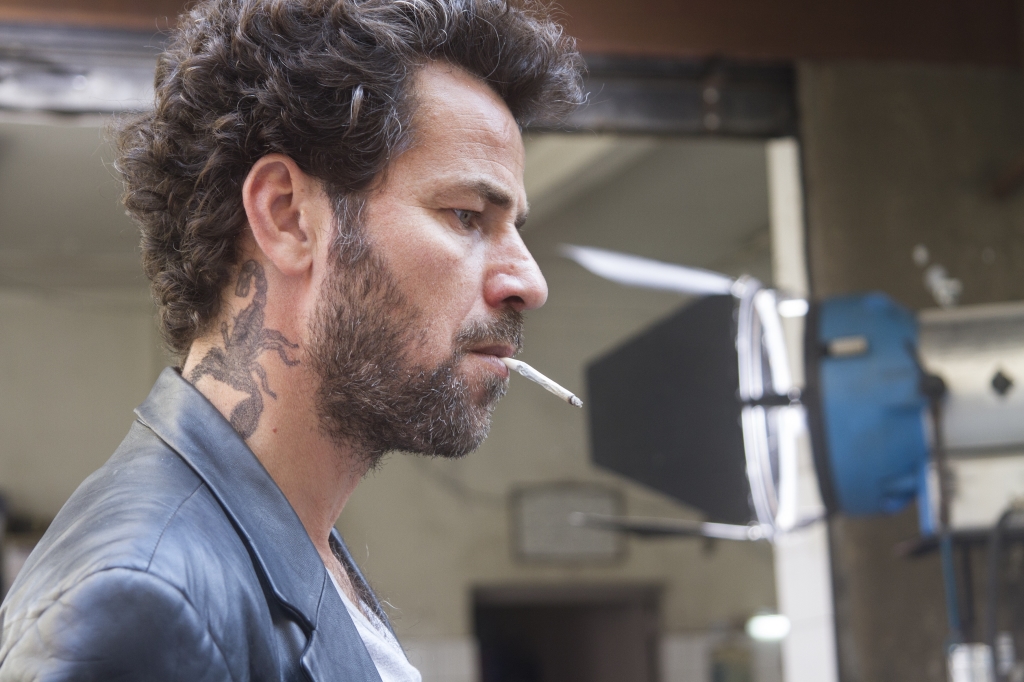

In other words, in Beirut Hold’em, which hits the halls next Thursday, we follow the story of Zico (Saleh Bakri) and his childhood friends in the famous neighborhoods of Beirut. A man in his 40s has just been released from prison trying to get his life back on track and win back his girlfriend Carol (Rana Alamuddin) after she suffered a broken heart and lost her sister in a car crash. Without revealing details, Zico will face a series of inevitable failures and tragedies in light of the darkness that surrounds his living conditions in Beirut. However, the film is not 100 percent dark. On this occasion, Cammoon commented in an interview with us: “The society we live in is full of contradictions, and so is life. So no day is like another, just like no one else’s fate and fortune are alike. We ask ourselves if life is worth living. After all, this is everyday life and continuity. A glimmer of hope and a smile gives meaning to life and makes us feel that life is worth living in general, and it doesn’t just apply to movie characters. This is the result of my observation. I observe our society and then I show it the way I see it in my films. When I write a work, I do it in a way that I see and feel without effort. Our lives are made up of these contradictions. We laugh at the drama and our problems.”

On the other hand, Kammoon admits that film is often the result of his obsession: “Revelation is always a mixture of things. Ideas come every day. But for an idea to become a movie, we need a lot of passion and attraction to keep working. We are not in a country where film production is abundant and we have the luxury of making a film every six months. The director has to be ready to make a film here. A mixture of desires and obsessions made me turn Beirut Hold’em from idea to idea and then to a movie. I think I act on the impressions I get from things, mixing obsessions and ideas and making them mix.”

Kammoon completed Beirut Hold’em in 2019, before the economic crisis, but what happened after the outbreak of Covid-19 and the financial crisis prevented the release of the film until this year. Note that it was shown at the “Red Sea Festival” in Saudi Arabia in December last year. Beirut, with its everyday details, streets and dangers, is present in the film, and the hardships experienced by its characters are very applicable to the feelings of the majority of its inhabitants today, in light of the dire crisis they are facing. The director said the film was completed before the crisis, adding: “What we see here and feel about the crisis was filmed before it. It is the result of observation, imagination and feeling, more like an organic matter. Everything you shoot is connected to each other. From the short film Shadow, which he released in 1994 as a sequel to Falafel, until now, I have always relied on observation and feelings, trying to express them in the way I know how.”

The film takes its title from the famous game, clearly referring to the gambling life in Beirut, as well as the life of Zico and his friends in this city, which has new and different challenges for them every day. maybe more difficult than before. On this occasion, Kammoon commented, “This is why we do everything quickly, because we don’t know what awaits us in the next few moments. Our life becomes a game of chance. We live in moments of drama to the maximum, as well as moments of happiness. If a man loves, he must finish the adventure, whatever the outcome, be it destruction or joy, and the same if he hates it. I know these things because I live them. This is the heart of the film.

Scenes and rituals express the passage of time in cinema.

Religious symbols and rituals have their place in the film, from church weddings to baptisms and burials. Cummins likes to conclude the social context in which his characters live from: “Zico belongs to that category. I don’t like movies where we don’t know where the person is. I’m not talking about religion here, but I want to show where it comes from. The characters we don’t know where they come from, we feel they don’t have arms, legs or faces, and how I use these rituals in the stages of life. There are stations in the narrative and many layers. Scenes and rituals express the passage of time in cinema in an attempt to mirror the passage of time in life.

* Beirut Hold’em in the halls from Thursday

Source: Al-Akhbar