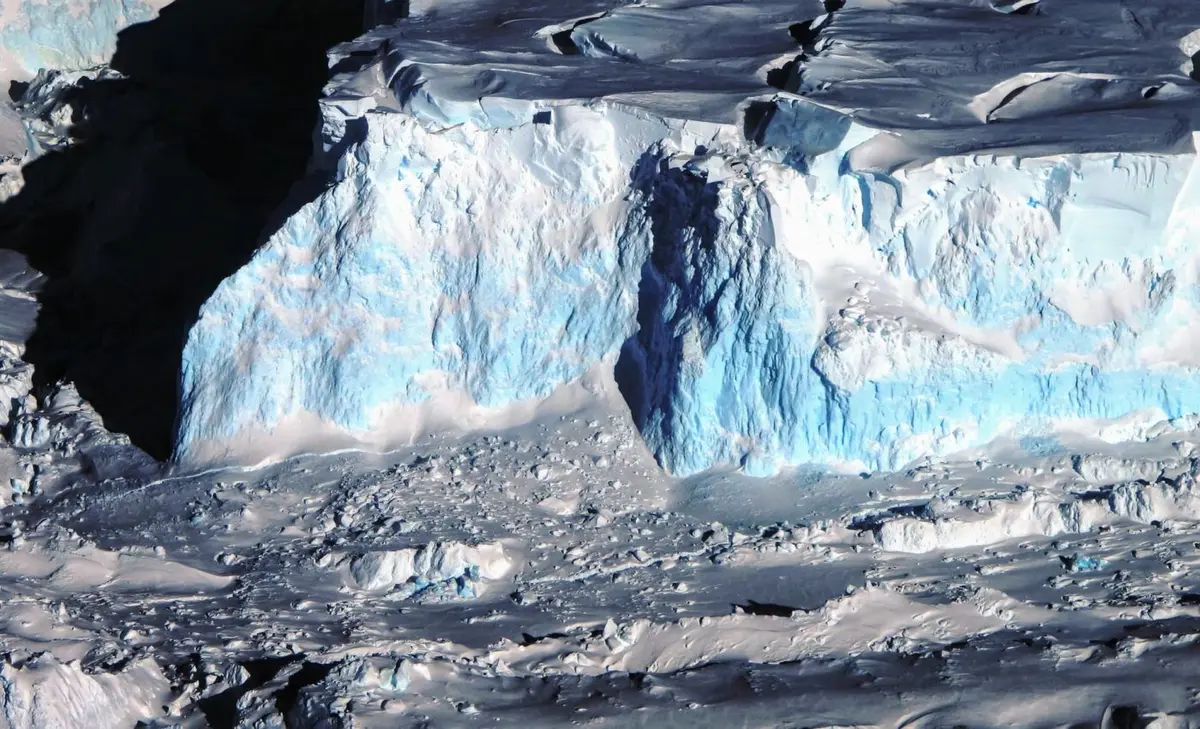

In remote Antarctica, the melting of a massive glacier is accelerating. The giant, called the Thwaites Glacier, is often referred to as the Doomsday Glacier. Experts leading the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC) have been studying its dynamics since 2018.

Researchers are zooming in on Thwaites, breaking through the ice and using underwater robots to comprehensively examine the massive glacier and understand its potential decline.

The Retreat of the Doomsday Glacier

The extensive and painstaking research has revealed some very disturbing findings. According to Rob Larter, a marine geophysicist at the British Antarctic Survey and a key member of the ITGC team, the Thwaites Glacier is not just retreating, it is retreating at an incredible rate and will continue to grow in the future.

“Thwaites has been retreating for over 80 years, accelerating significantly in the last 30 years, and our findings suggest it will retreat even faster,” Dr. Larter said.

The doomsday glacier is collapsing

There is little optimism about future predictions. Scientists predict that the Thwaites Glacier and the Antarctic Ice Sheet could collapse completely within the next 200 years.

The Doomsday Glacier holds enough water to raise global ocean levels by more than 2 meters. That kind of sea level rise could inundate coastal communities around the world, from Miami to London, from Bangladesh to the Pacific islands.

What’s worse is that Thwaites is acting like a cork, preventing the massive Antarctic ice sheet from flowing into the ocean. A doomsday glacier collapse could cause ocean levels around the world to rise by a staggering 3 metres.

Thwaites Glacier grounding line

Thwaites Glacier, with its sheer size and surprising features, poses a serious challenge for scientists. The topography of the area slopes downward, exposing more ice to the relatively warmer ocean water as it melts. To navigate these unique environments, researchers are using innovative technologies such as Icefin, an underwater robot that resembles a torpedo.

Icefin was sent to the Thwaites Glacier grounding line, a dangerous point where the glacier breaks away from the seabed and begins to float. For Kia Riverman, a glaciologist at the University of Portland, the first glimpse of the grounding line passing through Icefin was an iconic moment equal in emotional impact to the moon landing.

Rapid melting of Thwaites Glacier

Images transmitted from the Icefin vessel showed the glacier melting in unpredictable ways, with warm ocean water seeping through deep cracks and step formations in the ice, disrupting the glacier’s stability.

But the discoveries don’t stop there. Scientists also used satellite and GPS data to study the effects of tides and found that seawater can penetrate up to 6 miles beneath Thwaites. This infiltration of seawater bubbles up the warm water beneath the ice, causing rapid melting.

These discoveries led to further research into Thwaites’ history through analysis of marine sediment cores. University of Houston professor Julia Wellner determined that Thwaites’ rapid decline began in the 1940s and was likely triggered by a strong El Niño.

Thwaites’ irreversible comeback

Despite Thwaites’ rapid retreat, there was a glimmer of hope amid the gloomy statements: computer simulations showed the likelihood of ice shelves collapsing, which would cause a domino effect of icebergs crashing into the ocean, was lower than previously feared.

But the Doomsday Glacier is far from safe. Scientists predict that Thwaites and the Antarctic ice sheet behind it could disappear in the 23rd century. Whether humans can stop burning fossil fuels in the near future (which is currently unpredictable) may be too late to prevent the collapse of the Doomsday Glacier.

Joint efforts against climate change

The potential fate of Thwaites Glacier underscores the vital need for a global response to climate change. Collaborative projects like ITGC are critical for pooling global expertise and resources. To solve problems related to Thwaites Glacier, scientists share data and conduct interdisciplinary research spanning oceanography, geology and climatology.

This combined effort offers a glimmer of hope that humanity can develop effective strategies to mitigate the effects of sea level rise and climate change through collective innovation.

Vulnerable areas of Antarctica

Thwaites Glacier is of great interest because of its potential impact on global sea levels, but we also need to pay attention to other sensitive areas of Antarctica. The interaction of different glaciers with the Southern Ocean is a complex puzzle that researchers are trying to solve.

By understanding these dynamics, scientists are working to better predict scenarios and timing of global sea level rise. This research can also inform climate policy and adaptation strategies for coastal cities around the world.

Uncertainty about the future

At the end of this in-depth research phase, the ITGC team emphasizes that further research is needed to truly understand this complex glacier.

“Despite the progress we’ve made, we still feel a deep sense of uncertainty about the future,” said Eric Rignot, a glaciologist at the University of California, Irvine, who is part of the ITGC. “I am very concerned that this part of Antarctica is already in a state of collapse.”

Source: Port Altele