Research suggests that the “absolutely unique” wolf-like Tasmanian tigers that thrived on the island of Tasmania before they went extinct in 1936 may have survived in the wild for much longer than previously thought. Also, the odds of them still alive today are very low, according to experts.

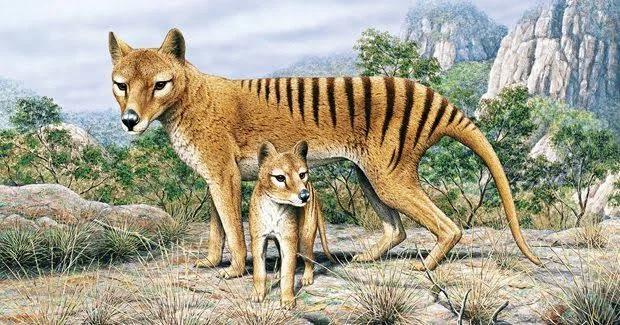

Also known as Thylacines (Thylacinus cynocephalus), Tasmanian tigers were carnivorous marsupials with distinctive stripes on their lower backs. The species was first found in Australia, but disappeared from the mainland about 3,000 years ago due to human persecution. It continued on the island of Tasmania until a government bounty imposed by the first European settlers in the 1880s decimated the population and drove the species to extinction.

“Tylasin was completely unique among living marsupials,” said Andrew Pask, professor of epigenetics at the University of Melbourne in Australia, who was not involved in the new study. “Not only did it have a similar appearance to the iconic wolf, it was also our only apex predator. Apex predators form extremely important parts of the food chain and are often responsible for stabilizing ecosystems,” Pask said in an email.

The last known thylacine died in captivity at the Hobart Zoo in Tasmania on September 7, 1936. According to the Thylacine Integrated Genome Improvement Laboratory (TIGRR), which Pask leads, which aims to bring Tasmanian tigers back from the dead, it is one of the few animal species with a definitive extinction date known.

But scientists now say thylacines probably survived in the wild until the 1980s, and with “a little luck” they’re still circulating today. In a study published March 18 in the journal Science of The Total Environment, researchers analyzed more than 1,237 reports of thylacine observations in Tasmania since 1910.

The team evaluated the reliability of these reports and where tilasin may have survived after 1936. “We used a new approach to map the geographic model of its decline in Tasmania and predict the extinction date by taking into account many uncertainties,” said Barry Brooke, professor of ecological sustainability at the University of Tasmania and lead author of the study.

The researchers suggest that thylacines may have survived in remote areas as late as the 1980s or 1990s, with the earliest extinction date to be in the mid-1950s. Scientists believe several Tasmanian tigers may still be hiding in the state’s southwestern desert.

But others are skeptical. “There is no evidence to support any of the observations,” Pask said. “One such interesting thing about tylasin is how it became so wolf-like and so different from other marsupials. Therefore, it is very difficult to distinguish a thylacine from a dog, even from afar. This is probably why it never became a dead animal or net We continue to make so many observations, even though we haven’t found an image.”

Pask said that if thylacines had survived long in the wild, one would have encountered a dead animal. However, “it may now be possible [у 1936 році] some animals survive in the wild,” Pask said. “If there were survivors, there were very few.”

While some people are searching for surviving Tasmanian tigers, Pask and his colleagues want to revive the breed. “Because of the recent extinction of the tilacine, we have enough good quality samples and DNA to do just that,” Pask said. Said. “Tylasin was also the result of an unnatural human extinction, and more importantly, the ecosystem in which it lived still exists, so there is room to return.”

According to the National Museum of Australia, stopping extinction remains controversial and extremely difficult and expensive. Advocates of the revival of thylacines say the animals can contribute to conservation. “Tylasin will definitely help restore the balance of the ecosystem in Tasmania,” Pask said. “In addition, the key technologies and resources created by the End Thylacine Extinction Project are critical to the conservation and protection of our now endangered marsupial species.”

However, opponents say ending extinction will distract attention from preventing further extinctions, and a resurgent thylacine population will not be able to sustain itself. “There is no possibility of recreating a sufficient sample of individual genetically diverse thylacins to survive and persist after release,” said Cory Bradshaw, professor of global ecology at Flinders University.

Source: Port Altele