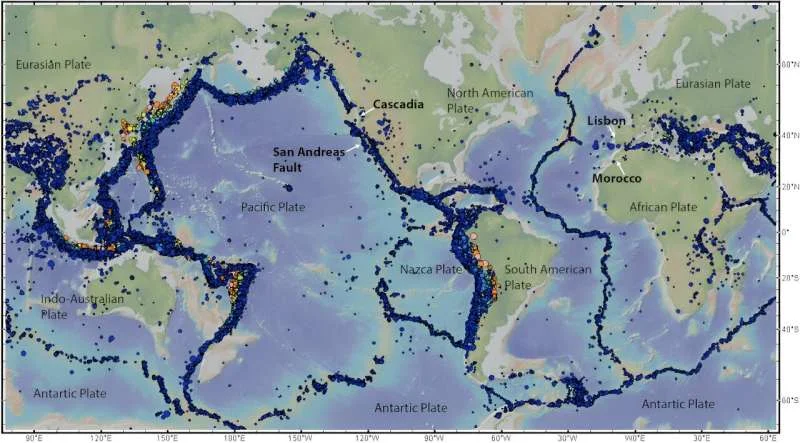

Earthquakes, large and small, occur every day in areas that cover the globe like the seams of a baseball. Most of them don’t bother anyone, so they don’t make the news. But every once in a while, somewhere in the world, a terrible earthquake strikes people with terrible destruction and great suffering.

The 6.8 magnitude earthquake that occurred in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco on September 8, 2023 shook ancient villages and left thousands of people under rubble. A large area of Turkey and Syria was destroyed by two powerful earthquakes that occurred back to back in February 2023.

The Earth’s crust crashes into itself and breaks apart

Earthquakes are part of Earth’s normal behavior. They are formed by the movement of tectonic plates that form the outer layer of the planet. You can think of the plates as a more or less rigid outer shell that must move to allow the Earth to release its internal heat.

These plates support continents and oceans and are constantly colliding with each other in slow motion. Cold, dense oceanic plates sink beneath continental plates and return to the Earth’s mantle in a process known as subduction. When the oceanic plate sinks, it drags everything with it, opening a crack elsewhere that is filled with hot material rising from the mantle, which then cools. These rifts are long chains of underwater volcanoes known as mid-ocean ridges. Earthquakes accompany both subduction and rifting. In fact, this is how plate boundaries were first discovered.

In the 1950s, when a global seismic network was established to monitor nuclear testing, geophysicists realized that most earthquakes occurred along relatively narrow bands that surrounded the edges of ocean basins, as in the Pacific, or passed right through the middle of the basins. As in the Atlantic.

They also observed that earthquakes that occur along subduction zones are shallow on the ocean side, but travel deeper beneath the continent. If you plot earthquakes in 3D, they will detect plate-like features following plates subducted into the mantle.

Experiment: How does an earthquake work?

To understand what happens during an earthquake, put your palms together and press with some force. You are modeling a plate boundary fault. Every hand is a plate, and the surface of your hands is wine. Your muscles are a tectonic plate system.

Now add a little forward on the right side. As the forward force overcomes the friction between your palms, you will eventually see it bounce forward. This sudden forward movement is an earthquake. Scientists explain earthquakes using a theory called elastic rebound theory.

Fast plates move at rates of up to 8 inches (20 centimeters) per year, primarily due to the subduction of oceanic plates in subduction zones. Over time, they stick together due to friction at plate boundaries. The attempted movement deforms the boundary region of the plate elastically, like a stretched spring. At one point, the accumulated elastic energy overcomes friction and the plate shakes forward, causing an earthquake.

However, the forces pushing the plate do not stop, so the plate boundary begins to generate elastic energy again, causing another earthquake, perhaps soon, perhaps in the distant future.

In the oceans, plate boundaries are narrow and distinct because the underlying rocks are very hard. However, within continents, plate boundaries often represent large, deformed areas of mountainous land cut by many faults. Even if the plate boundary is disabled, these faults can continue for years. Therefore, sometimes earthquakes occur far from plate boundaries.

Earthquakes, fast and slow

The cyclic behavior of faults allows seismologists to statistically evaluate earthquake risks. Fast-moving plate boundaries, such as those along the Pacific Rim, rapidly accumulate elastic energy and have the potential for frequent, large-magnitude earthquakes.

Slow-moving plate boundary faults take longer to reach critical state. Along some faults, hundreds or even thousands of years can pass between major earthquakes. This gives time for cities to grow and for people to lose their ancestral memories of past earthquakes.

An example of this is the earthquake in Morocco. Morocco lies on the border between the African and Eurasian plates, which are slowly colliding with each other. The vast mountain belt extending from the Atlas Mountains in North Africa to the Pyrenees, the Alps, and most of the mountains in Southern Europe and the Middle East is the product of this plate collision. But because these plate movements near Morocco are slow, large earthquakes do not occur that frequently.

We’re getting ready for the big one

An important fact about destructive earthquakes is that in most cases earthquakes destroy buildings, not people.

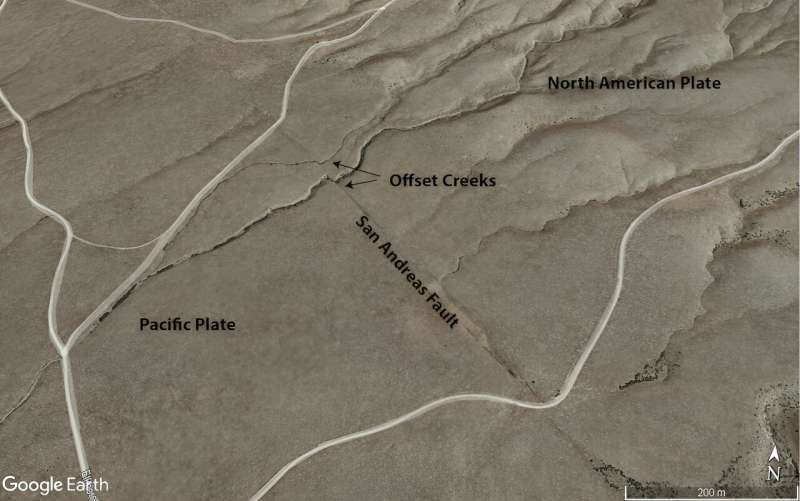

Most Americans have heard of the San Andreas Fault in California and the seismic risk of San Francisco and Los Angeles. The last major earthquake along the San Andreas Fault occurred in 1989 at Loma Prieta in the San Francisco Bay Area. The magnitude 6.9 earthquake was comparable to the earthquake in Morocco, but killed 63 people compared to thousands more. This is largely because building codes in earthquake-prone U.S. cities are now designed to support structures when the Earth shakes.

The exception is tsunamis, which are huge waves that occur when an earthquake shifts the seafloor and displaces the water above it. The tsunami that hit Japan in 2011 had terrible consequences despite the quality of engineering work in coastal cities. Unfortunately, scientists cannot predict exactly when an earthquake will occur; they can only assess the danger. Source

Source: Port Altele