Radiocarbon dating and DNA analysis showed that the entire skeleton found in a grave in a Gallo-Roman cemetery did not belong to a single person, as scientists had previously believed, but consisted of the bones of seven people. Many of them lived in different centuries. The assembled skeleton reflects true anatomy skill and knowledge, but who put it together and why remains a mystery.

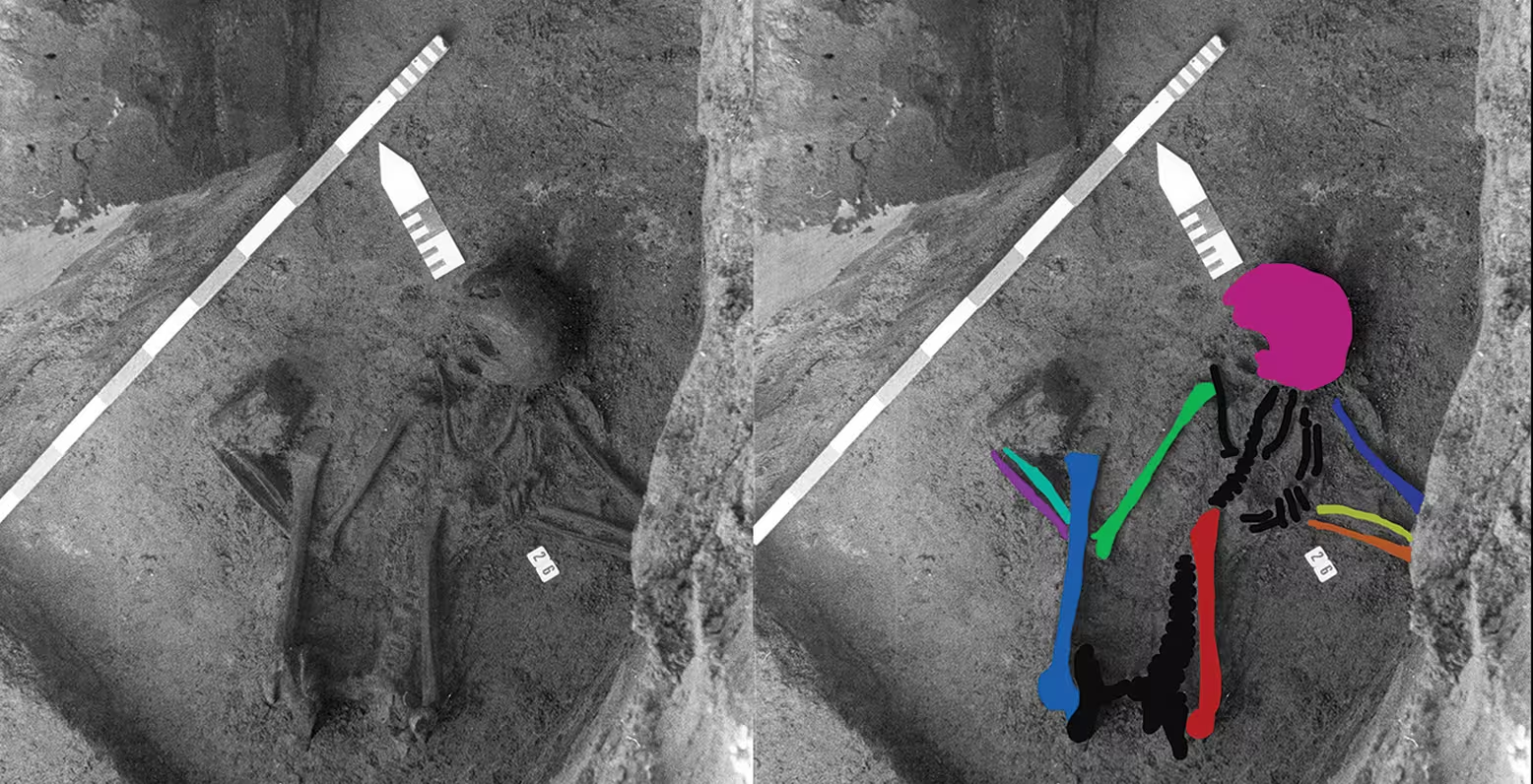

In the 1970s, at the cremation cemetery in the town of Pomroel (Belgium), archaeologists unearthed a grave with the skeleton of a person lying in the embryo position: on his right side with his legs pulled towards him. A Roman bone pin placed next to the head led scientists to believe they had found a Roman tomb dating to the 2nd and 3rd centuries. The skeleton was exhibited at the Malgre-Tut Museum in the city of Viruanval.

This finding was analyzed by many scientists and they were confused by some oddities. The lateral position of the skeleton is characteristic of Neolithic and Early Bronze Age graves, and in Roman times people were buried on their backs. The vertebrae also appeared to be a mix of bones from young and old, perfectly aligned. The femur looked very large.

In 2024, an international team of archaeologists led by Barbara Veselka (Barbara Veselka) from the Free University of Brussels examined the skeleton once again. In addition to radiocarbon dating of the hand and foot bones, skull and five fingers, scientists also analyzed DNA taken from a bone of the skull.

Surprisingly, the researchers discovered that the skeleton was actually “moulded” from the remains of at least seven unrelated individuals (male and female) who lived in the Neolithic era approximately 4212-4445 years ago.

Radiocarbon dating of the skull was inconclusive, but DNA analysis showed that it belonged to a Gallic-Roman woman who lived 2,500 years ago. Interestingly, his DNA was similar to that of two teenagers buried in a Roman cemetery about 1,800 years ago, 150 kilometers east of Pomroel. So the woman and the young man were relatives.

Numerous examples of postmortem manipulation of the human body and body parts are known in the archaeological cultures of Europe, starting from the Paleolithic and continuing through the Roman period. Such practices included repeated burials, making skeletons from other people’s bones, and even making tools and equipment from the bones of the dead.

However, the find at Pomroel is the first example of a composite skeleton spanning such a wide range of age groups and cultures in the history of European archaeology. Moreover, it is composed so elegantly that it speaks of the high skill of the “author”, who has excellent knowledge of human anatomy.

It is not yet clear who made the skeleton. Veselka explained that Bronze Age tribes could collect bones from different graves to create a complete skeleton, a symbol of unity. Shortly afterwards, the Romans added a skull out of respect for the dead: this could happen if they accidentally damaged the original Neolithic skull, for example, during the construction of a cremation necropolis.

The results of the research can be found in the article published in the journal. Antiquity.

Source: Port Altele