Using observations from NASA-German satellites, an international team of scientists found a significant decrease in the total amount of freshwater on Earth since May 2014. The average amount of freshwater on land, including liquid surface water and underground aquifers, was 2.2 to 290 cubic miles (1,200 cubic kilometers) below the average level from 2015 to 2023, according to a report published in the journal Surveys in Geophysics. This reduction is equivalent to more than two and a half volumes of Lake Erie.

Matthew Rodell, a hydrologist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and one of the study’s authors, said: “This shift may indicate that Earth’s continents are entering a steadily drier phase.” Researchers used data from the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites operated by the German Aerospace Center, the German Earth Sciences Institute, and NASA to measure Earth’s gravity fluctuations, which indicate changes in the mass of water above and below the surface.

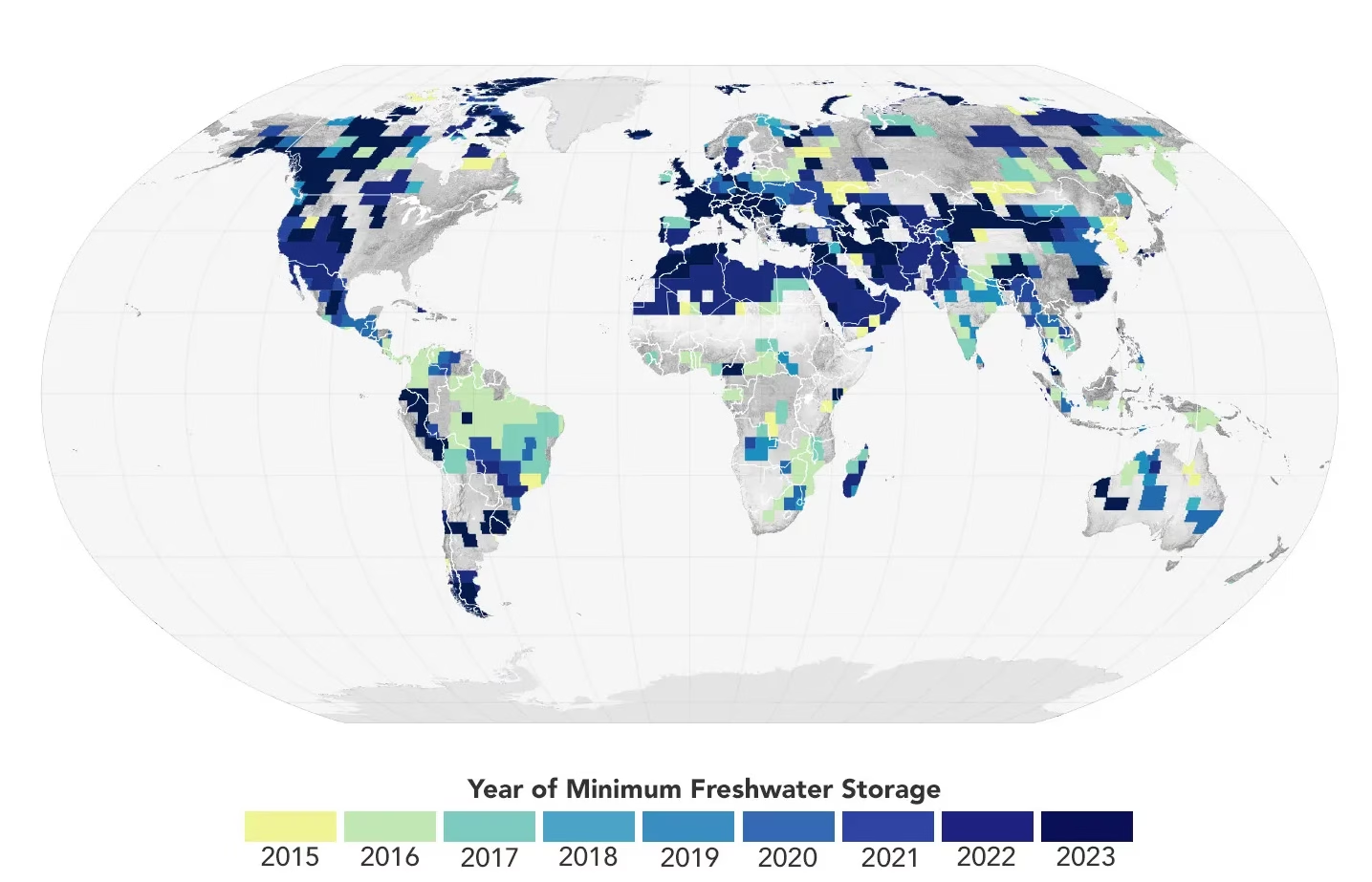

The decline in global freshwater resources began with a large-scale drought in northern and central Brazil, and was followed by a series of major droughts in Australasia, South America, North America, Europe and Africa. Rising ocean temperatures in the tropical Pacific from late 2014 to 2016 culminated in one of the most significant El Niño events since 1950, leading to changes in atmospheric jets that altered weather and precipitation patterns worldwide. But even after El Niño subsided, global freshwater supplies did not recover. In fact, 13 of the 30 most intense global droughts that GRACE has observed have occurred since January 2015.

Global warming may contribute to the continued depletion of freshwater resources because higher temperatures cause the atmosphere to hold more water vapor, leading to more extreme precipitation. Although total annual precipitation and snowfall do not vary much, long periods between heavy rainfalls cause the soil to dry and thicken, reducing the amount of water the soil can absorb when it rains. NASA Goddard meteorologist Michael Bosylowicz noted: “The problem when extreme precipitation occurs is that water is absorbed and eventually runs off rather than replenishing groundwater.”

While there are reasons to suspect a connection between dwindling freshwater supplies and global warming, it can be difficult to definitively link the two phenomena, said Suzanne Werth, a hydrologist and remote sensing expert at Virginia Tech who was not involved with the study. uncertainty in climate predictions and errors in measurements and models.

Time will tell whether global freshwater supply will recover to pre-2015 levels, remain stable, or continue to decline. But given that the nine warmest years in modern temperature history coincided with a sharp decline in freshwater supplies, Rodell said, “We don’t think that’s a coincidence, and we think it could be a harbinger of things to come.”

Source: Port Altele