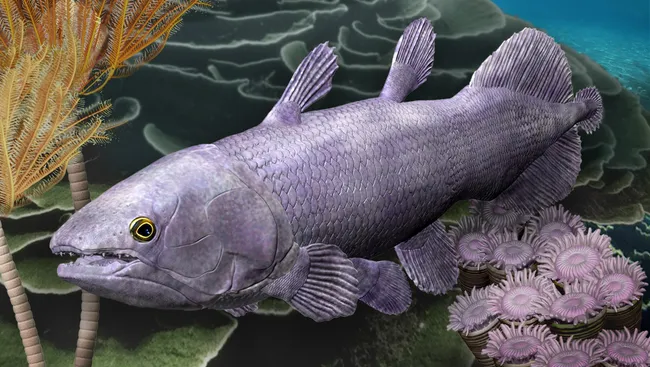

What do ginkgo (tree), nautilus (mollusk) and laticrug (fish) have in common? They don’t look alike and aren’t biologically related, but some of their evolutionary history is strikingly similar: These organisms are called “living fossils.” In other words, they appear to have survived the transformations that normally occur through evolution over time.

Latimer has been called a “living fossil” for 85 years because it reminds us of a bygone era, the age of dinosaurs. These fish belong to the sarcopterygians, a group that also includes breathing fish (lungfish) and quadrupedal fish, including humans. Quadrupeds are vertebrates (animals with backbones) that share common anatomical features, including the humerus (foreleg bones), femurs (hind leg bones), and lungs.

Few vertebrate species excite as much curiosity as the laticulus, both because of the fascinating history of its discovery and its status as a “living fossil.” At most two existing species of laticum that managed to survive this long evolutionary process are now in danger of extinction.

So does Latimer really deserve this label? So what do Latimula fossils tell us about this evolutionary curiosity?

In this regard, as a paleontologist, evolutionary biologist and ecological modeler, in this article we take a new look at the 410 million-year history of Latimer evolution. Using the latest available technological advances and innovative analytical methods, we are working to better understand the evolution of these fascinating species, often referred to as ‘living fossils’.

Big discovery in Western Australia

Our research, recently published in the journal Nature CommunicationIt describes and describes fossils of the 380-million-year-old extinct species laticum discovered in Western Australia.

These remarkably well-preserved fossils come from an important transitional period in the long evolutionary history of this fish species. This study is the result of international collaboration between researchers affiliated with institutions in Canada, Australia, Germany, Great Britain and Thailand.

“Living fossils”: a contested concept

Charles Darwin was the first person to use the term “living fossil” in his book. “The origin of species” in 1859, to indicate species of living things that he considered “abnormal” or “abnormal” compared to others at the time. Although the concept was not clearly defined in Darwin’s time, hundreds of biologists have embraced the concept since then. However, the term “living fossil” and the type of species that deserve this title remain a matter of debate in the scientific community.

In general, for a taxon (scientifically classified group or entity) to be considered a “living fossil” it must meet certain criteria: It must belong to a group that has existed for millions of years, has changed little morphologically over time, and Its relatives have so-called primitive features relative to their evolutionary relatives. has.

Fascinating history: Latimerias through the ages

More than 175 Latimer species fossils survived from the Lower Devonian Period (419-411 million years ago) to the end of the Cretaceous Period (66 million years ago). In 1844, Swiss paleontologist Louis Agassi singled out a special group of fossil fish that he called the Latimer order.

For about a century, Latimers were thought to have become extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period, about 66 million years ago. During this time, almost 75 percent of life on Earth became extinct, including most dinosaurs, except for the ancestor of birds.

Then, on December 22, 1938, Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, curator of the East London Museum in South Africa, received a call from a fisherman who had caught a rare and strange fish. He realized it was an unknown species and contacted South African ichthyologist (fish biologist) JLB Smith. Smith confirmed that this was in fact the first living Latimyr ever seen.

In 1939 Smith named the genre Latimeria chalumnaealso known as gombessa. Since then, the species, discovered on the east coast of Africa, near the Comoros Archipelago, in the Mozambique Channel and off the coast of South Africa, has attracted great scientific interest.

In 1998, a second living species of Latimeria was discovered near the Indonesian island of Sulawesi. Latimeria menadoensis (Indonesian name ikan raja lautroyal sea fish). These two species are the only surviving members of an ancient lineage that appears to have evolved little over the past few million years. After opening Latimeria chalumnae Latimerias were considered vertebrates whose body shape changed little over time, indicating slow evolution.

Ngamugawi or “old fish”

In our study, we describe a new species of laticum from the Devonian period of Western Australia. We named him Ngamugawi wirngarri . Ngamugawi It means “old fish” in the Guniandi language, the language of Australian aboriginals in the Kimberley region. wirnharry It honors Guniandi’s revered ancestor, Virngarri.

Ngamugawi wirngarri It was discovered in the Gogo geological formation, known worldwide as an extraordinary fossil site. Gogo is famous for the three-dimensional preservation of numerous fish fossils and sometimes even soft tissues such as hearts and muscles. More than 50 species of fish fossils have been discovered in Gogo to date. This diverse group of fish, along with a group of marine invertebrates, coexisted on a coral reef in the warm Devonian sea about 380 million years ago.

Evolution is more complicated than it seems

Our study shows that latimers evolved rapidly early in their history, during the Devonian, but that evolution slowed down thereafter. The fact that evolutionary innovations almost ceased after the Cretaceous period suggests that some features of Latimeria are as follows: LatimeriaIt looks like it’s frozen in time.

However, other characteristics, such as body proportions, continued to evolve at a normal rate during the Mesozoic Era (252-66 million years ago). Despite the fact that the shape of the body has changed very little, this confirms the idea Latimeria Because it is a “living fossil,” the evolution of its skull shape has never stopped, making the label questionable.

Of all the environmental variables examined, the activity of the tectonic plate has the most significant impact on Latimer evolution rates. New latimer species emerged more frequently during periods of intense tectonic activity when new habitats were created or fragmented.

Ngamugawi’s opening performances, That Latimires have not changed for millions of years. Their slow evolution suggests that they are not “living fossils” but are in fact the result of a complex evolutionary history.

Source: Port Altele